Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen, right, and China’s ambassador to Cambodia, Wang Wentian, press buttons during a groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of an expressway from Phnom Penh to Bavet city, in Phnom Penh, June 7, 2023.

By Sun Narin and Han Noy, VOA Khmer

PHNOM PENH, CAMBODIA — China-funded development projects in Cambodia are a mixed bag for the country as some see them as an opportunity to improve the country’s poor infrastructure while others raise concerns about Cambodia’s economic dependence on China, according to analysts.

A month before Cambodia’s national elections, Prime Minister Hun Sen announced the latest major infrastructure project financed by Beijing, an expressway connecting Phnom Penh to Bavet on the country’s eastern border with Vietnam.

The 135-kilometer road will cost an estimated $1.37 billion and follows the opening of a $2 billion China-funded expressway connecting Phnom Penh to Sihanoukville, Cambodia’s major ocean port city, last year.

“The expressways will be done before I die,” Hun Sen said in a groundbreaking ceremony for the Phnom Penh-Bavet highway in mid-June.

The timing of the announcement underlines Hun Sen’s reliance on Beijing to deliver economic progress as he nears four decades in power, a relationship that analysts warn is leaving Phnom Penh beholden to Beijing.

Enhancing image

Chhay Lim, a visiting fellow at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at the Royal University of Phnom Penh, said the China-funded infrastructure projects “not only yield benefits for the general public but also play a crucial role in bolstering the legitimacy of the ruling regime.”

“This form of legitimacy, known as economic performance-based legitimacy, is underscored by the positive socioeconomic impact resulting from the influx of Chinese investments. Notably, as the upcoming elections approach, the newly announced Chinese expressway projects will further enhance a positive image of the Cambodian government,” he told VOA Khmer.

The ruling Cambodian People’s Party is again facing an election without a serious opposition challenger after the government in May barred the Candlelight Party from competing over missing paperwork.

Still, indicators like voter participation and spoiled ballots will be watched closely as an indicator of general unrest. Hun Sen has positioned his eldest son, General Hun Manet, to succeed him, though the timeline remains unclear.

Hun Sen has made no apologies for welcoming Chinese largesse, which comes without the Western requirements on democracy and human rights. But as Chinese financing has fueled construction in Cambodia over the past decade, fears are growing that Cambodia will take on unmanageable debt, leaving it at Beijing’s mercy.

The expressway projects are not structured as loans, but rather as “build-operate-transfer” (BOT) models in which a Chinese company is paid back through ongoing revenue before ultimately handing over control to Cambodia.

“Relying too heavily on Chinese investors to underwrite public projects in Cambodia means the real patrons are not the Cambodian people, but the investors and their country of origin in particular: China,” said Sophal Ear, an associate professor at the Thunderbird School of Global Management at Arizona State University.

“Cambodia should not rush to develop more expressways with Chinese investors, because it should shop for the best possible deal instead of allowing these investors to build a road and then operate it for many years, only to subsequently transfer it back to Cambodia after its economic value may be gone,” he added.

Tolls for half century

The Chinese-state owned firm CRBC will collect tolls for 50 years under the BOT agreement after the expressways open, according to Cambodia’s Ministry of Transportation.

The Sihanoukville and Bavet expressways could be part of an even larger network, as Beijing seeks to further expand its global influence through the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy that aims to connect China with Africa and Europe via land and maritime networks.

Last month, Hun Sen said the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) is studying the feasibility of expressways to Siem Reap and Poipet City on the Thai border, which would cost around $4 billion.

Chhay Lim, who is also affiliated with Cambodia’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies, said he thought the BOT model was a “smart move” as it “will alleviate the current debt burden, which has reached approximately $10 billion.”

“In the process of project implementation, the government must ensure an effective and efficient policy coordination, transparency and, most importantly, mitigate any potential negative impacts that may affect the local community,” he said.

All the expressways are financed and constructed by China Road and Bridge Corporation (Cambodia), which is headquartered in Beijing and has offices in about 60 countries and territories.

Although CRBC’s earnings aren’t publicly released, its parent entity, the China Communications Construction Group (CCCG), recorded $119.9 billion in group sales in 2021, according to a Nikkei Asia report on December 13, 2022.

CCCG is the world’s third-ranked contractor in terms of overseas revenue, according to Engineering News-Record, a U.S. construction industry publication. It is also one of the biggest players in the Belt and Road Initiative.

Linking economies, watching rival

Xi launched the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013 to link the economies of Asia, Europe and Africa with highways, rail lines and power plants. It has also been a key element in China’s geopolitical rivalry with the United States, boosting Beijing’s economic and diplomatic clout around the world.

In a public event in May, Hun Sen said BRI has benefited Cambodia for 10 years as he lauded Xi’s initiative as a “win-win.”

Joining the expressway groundbreaking ceremony in early June, China’s ambassador to Cambodia, Wang Wentian, said the project was “the symbol of cooperation between China and Cambodia” and “a fruitful achievement of BRI.”

However, the U.S. has warned countries against taking on large projects under China’s BRI infrastructure strategy. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently shared her fears with lawmakers.

“I am very, very concerned about some of the activities that China engages in globally, engaging in countries in ways that leave them trapped in debt and don’t promote economic development,” Yellen said at a hearing in March.

Washington points to Sri Lanka, where Beijing gained control over its main port as debt repayment.

Hun Sen’s government argues that its borrowing remains under control, and that the BOT projects allow it to avoid a “debt trap.” According to the Ministry of Economy and Finance, Cambodia’s current foreign debt load of $9.47 billion (around 35% of its $27 billion GDP) last year can safely increase to around $12.62 billion in 2023.

Still, a report by the Kiel Institute in Germany in 2019 estimated that Cambodia was the sixth most indebted country as a share of GDP among 50 recipients of Chinese government loans and private debt.

And while both China and Cambodia have rejected suggestions of diplomatic quid pro quo, analysts say Hun Sen has been a reliable supporter of China’s interests on the global stage, amid rising tensions over the South China Sea and Taiwan in the region.

Last month, Cambodia held up ASEAN plans for regional military drills, saying it needed time to review a proposal put forth by Indonesia that would have angered Beijing.

Hun Sen has repeatedly praised China’s “no-strings-attached” diplomacy as relations with the West have deteriorated over his crackdown on dissent and the accompanying legal assault on the political opposition, according to political observers in Cambodia.

For many Cambodians, the expressway is a reason for celebration, and perhaps evidence of the prime minister delivering on his economic agenda. But communities facing eviction are worried about what their future will look like.

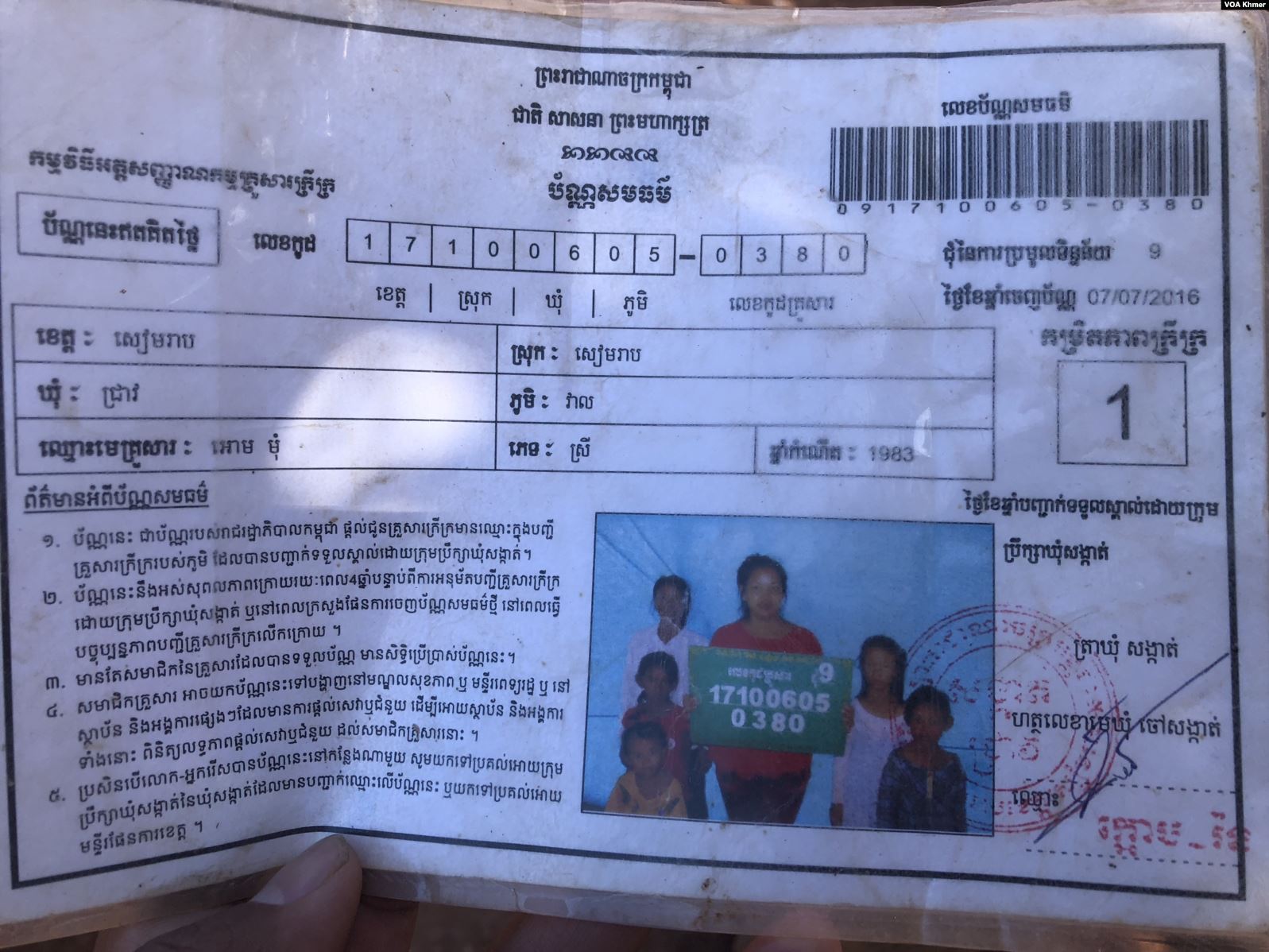

Sok Phouen, 49, owns a 700-square-meter patch in Kandal province, on the planned route to Bavet. She is worried she won’t be living there for long.

“[The company] makes a lot of profits. But villagers, as the victims, lose,” said the mother of four.

“Cambodia is close to China. That is why we can have an expressway,” she added.

Phouen’s neighbor, Pen Ny, 72, is also worried about losing her 1,200-square-meter parcel, with construction on the expressway set to be completed by 2027.

“I am scared of having no place to stay. I am worried because I don’t know where to go,” said the mother of six.

“We can’t deny anything these days. Whatever projects they want to do, they can do,” she added, pleading for fair compensation for her land. “Don’t make people miserable.”

PHNOM PENH —

PHNOM PENH —