By Sun Narin, VOA Khmer

Chreav commune, Siem Reap City – When Om Samath arrived at the provincial referral hospital last year to undergo eye surgery, she knew the operation would be performed free of charge.

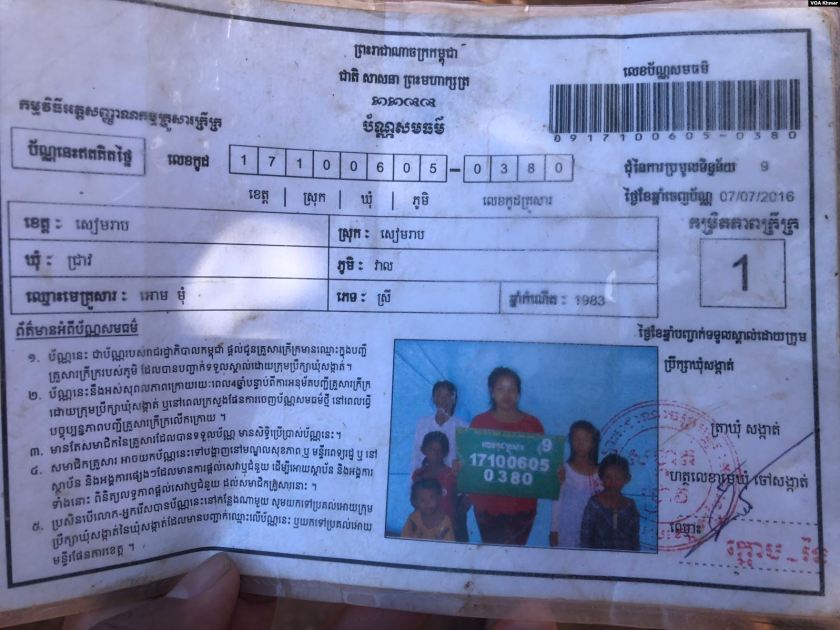

Two years earlier, her family was identified as one of the poorest in the commune and issued an Equity Card, a perk of the government’s IDPoor program that grants holders access to free treatment at state-run medical facilities.

What the 53-year-old widow didn’t expect was that once the operation was performed, her inability to pay would relegate her to the status of second-class patient for the duration of her two-week recovery. She received a daily food stipend of 5,000 riel, or about $1.25, but no follow-up care.

“They didn’t change the bandage on my eye as it should have been. I noticed that they changed others’,” Samath told VOA in an interview at the small tin-sided house she shares with her daughter, son-in-law and five young grandchildren.

“If I had had money, I would have given it to them so that they would have taken proper care of me,” she added, swinging her 1-year-old granddaughter to sleep in a hammock.

Frustrated and confused

The IDPoor program was launched by Ministry of Planning in 2006 with the support of the German and Australian governments, which sought to simplify the process for identifying vulnerable households and targeting free health care and other services. With an initial focus on rural Cambodia, the program expanded to urban areas in 2016.

“Before the project began its work, there was no standardized, universally recognized and nationally applied procedure for recognizing poor households in Cambodia,” according to Germany’s aid agency, GIZ. “This meant that poor households were unable to assert their rights to basic social services, such as free medical treatment.”

The Cambodian government claims the IDPoor program has been a success, with more than 600,000 Equity Cards — also known as poverty cards and cards for the poor — having been distributed to households across the country, benefiting an estimated 2 million people.

But more than a decade after the program was launched, recipients and non-recipients alike remain frustrated and confused about the criteria used to allocate the cards and the benefits bestowed on their holders.

“I thought that I would be given donations of rice and other food,” said Pork Kep, who, like Samath and many other grandmothers in rural Cambodia, takes care of her grandchildren while her adult children seek employment in urban areas — or abroad.

Kep, 46, suffers from headaches, high blood pressure and gastrointestinal issues. But instead of seeking treatment at the commune health center or provincial referral hospital, she self-medicates using pills purchased from a local pharmacy. The pills cost about $3 per week — a significant expense.

Her confusion about the Equity Card is exacerbated by the fact that scores of NGOs have, over the years, used the IDPoor database to deliver non-medical services such as food, clean water, agricultural assistance and educational opportunities.

San Chanbunsorn, 37, received an Equity Card in 2013 and, through a program at his daughter’s school, received a 25-kilogram sack of rice and a bottle of cooking oil every three months while his daughter was a student in grades 1 through 6.

“Now, I don’t get any more because my daughter is studying in Grade 7,” he said.

‘They wear gold’

Resentment is ripest among those without Equity Cards.

“I should be given one because I am so poor. Look at my house,” said Pha Chorvoin, 34, gesturing to her a home, a crude shack constructed of wooden planks and palm fronds.

Chorvoin earns $100 per month as a cook at a local restaurant; her husband makes about $6.50 a day as a construction worker. She has two children — a 4-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter — and is pregnant with a third.

“My children often get sick,” she said, suffering from frequent fevers, coughs and headaches as a consequence of poor sanitation.

Yet despite not having an Equity Card, they receive free medical treatment at the commune health center because the staff there know that her family is poor. When she is ready to deliver her baby, Chorvoin said, “they will give me free delivery,” explaining that the service would normally cost about $15.

While Chorvoin does not understand why she has not received an Equity Card, she is equally uncertain about why some other have — though she has some theories.

“Some people have the card, but they wear gold,” she said. “They are not really poor.”

“I think the distribution [of cards] is not fair yet. People who are close to the authorities get the cards,” she added.

“They only give the card to people they know,” agreed Chorvoin’s sister-in-law, Touch Saray, 35, adding that her family, too, has not received a card despite their dire circumstances.

Allegations of bias

Meas Nee, an independent social and political analyst, says such grievances are commonplace, and reinforced by widespread reports of unjust Equity-Card allocation and a two-tiered health care system.

“I think there is still not equal treatment at health centers,” he said. “People who have money get treatment first and the poor get it later.”

A common complaint, Nee added, is that families most in need of free health care — impoverished, indebted and undernourished — are passed over in favor of those with allegiances to the ruling Cambodia People’s Party (CPP) and ties to local officials.

“Some people are not very poor but they still get the card,” he said. “The government must make sure that there is no political bias in this process.”

This suspicion is rooted in decades of CPP rule; at the national and local level, government services are almost always controlled by party affiliates. In the lead-up to the 2018 election, the CPP undertook a nationwide campaign to register entire households as “CPP families.”

Kong Beub, the deputy chief of Chreav commune, denied allegations of bias in the IDPoor program.

“We give them out without considering different political preferences,” he said. “We announce the names publicly and people can complain.”

According to Beub, a little over 200 families in the commune hold Equity Cards, down from about 300 in 2017.

Keo Ouly, director of the Planning Ministry’s IDPoor department, agreed that the procedure for distributing Equity Cards was fair and transparent. “We have our process,” he said.

Poverty and debt

But Kdeub Savath, 33, who helped survey poor families in Chreav commune from 2013 to 2016, said this “process” was flawed, noting that local officials never followed up with families that received Equity Cards during his time as volunteer.

Of the card, he said: “Some people don’t make use of it. Some should get it, but they don’t.” The consequences of the latter, he added, are grave. “Some villagers have land, but they owe the bank. Some get ill, and if their illness gets serious, they can’t go for treatment.”

Indeed, many residents of Chreav commune — just a short drive from the tourist-choked center of Siem Reap City — suffer from severe poverty and paralyzing debt.

Although poverty in Cambodia has fallen sharply in recent years, 4.5 million citizens teeter just above the global poverty line, according to the World Bank. “The loss of just 1,200 riel (about $0.30) per day in income would throw an estimated 3 million Cambodians back into poverty, doubling the poverty rate to 40 percent,” Neak Samsen, a Bank analyst, wrote in 2014.

Boeung Bora, director of the Chreav health center, said that more than 100 families with Equity Cards — half of all card holders in the commune — seek free treatment at his facility each month.

“Mostly children with the flu and respiratory problems, and pregnant women,” Bora said. “We treat only minor problems. If it’s a serious problem, we send them to the provincial referral hospital.”

And when an obviously destitute patient show up without an Equity Card? “We also give them free treatment,” he said.

PHNOM PENH —

PHNOM PENH —